Discovery 1975-1976

The Story of Black Disco

“We believed in the music. They’re still a very big part of my life. Whenever I write new songs, I always have them in mind.” - Pops Mohamed

It’s 1975 in South Africa and an ambitious young musician and composer from Benoni named Pops Mohamed has his heart set on recording an album. He has some experience as a bandleader and is equipped with hip tastes and a demo tape, albeit just a snapshot of the sound he has in mind. He has no doubt about the right person to speak to, setting his sights on Rashid Vally, the record producer and proprietor of the Kohinoor music store in downtown Johannesburg.

Under the banner of Soultown Records, Vally first enters the domain of discerning jazz with the release of Gideon Nxumalo’s Early-Mart in 1970. Striking up a relationship with Abdullah Ibrahim, he reinvents his label as As Shams/The Sun in 1974 for the release of the Dollar Brand album Mannenberg - ‘Is Where It’s Happening’. The label’s inaugural offering is a breakout success that propels his independent operation into the mainstream with a manufacturing and distribution deal from Gallo Records. The future looks bright.

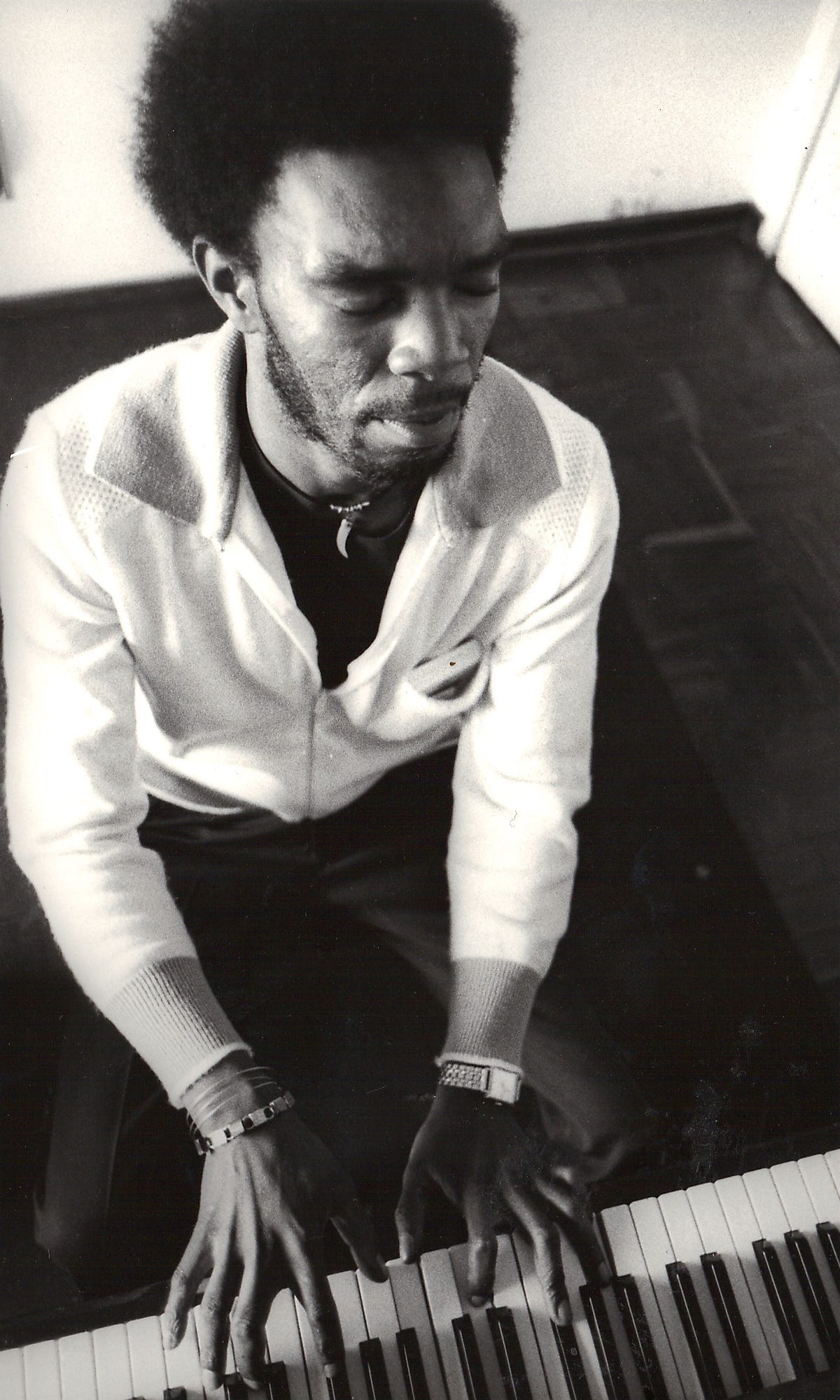

Pops Mohamed approaches Rashid Vally at the Kohinoor store. “What do you play?” Rashid asks. “Organ and guitar,” Pops replies. Mohamed takes guitar lessons at Johannesburg’s Dorkay House music hub during high school and admires the network of professional musicians who hang out there. His keyboard chops are self-taught and he’s crafted his skills on the Yamaha Electone, a popular electric organ that emerged in the late-1960s. He hands over a small reel containing a makeshift recording of a composition entitled “Dark Clouds.”

The track’s distinguishing sonic characteristic is the what the Electone’s manual refers to as the “Auto Rhythm Section,” a rudimentary built-in drum machine with a smattering of pre-sets (waltz, swing, rhumba etc.) connected to an adjustable tempo control and tone pedal. It’s unlikely that the designers of the Electone intended this feature to be more than a simple accompaniment for practicing but, presented on the demo tape, it evokes an avant-garde, proto-electronic alternate universe into which Mohamed casts his organ, stomping out the bass notes on the foot pedals and soaring melodically through the higher registers on the keys. Vally is enchanted. “That’s a great bass line,” he remarks.

“Dark Clouds” is an original composition but Pops Mohamed mines various sources to come up with the sound. At the heart of his formula is Timmy Thomas, the R&B singer who’s 1972 album Why Can’t We Live Together pioneers the minimalist combination of cosmic organ and drum machine. Mohamed is drawn to the spiritual palette of the organ with its roots in gospel, embraces the modernist aesthetic of the programmed drums and also connects with the social messages that Timmy Thomas promotes – calls for peace and unity in a politically polarised environment intent on stoking ethnic and racial tribalism. As for the bass line, he’s borrowed the ascending four-note backbone of Marvin Gaye’s 1973 hit “Let’s Get It On.” An irresistible groove, it’s the track’s secret weapon.

Pops Mohamed has come up with a formula that offers something soulful and soothing – a type of modern instrumental chill-out music that aspires to have healing properties and promote higher consciousness. As a spiritual man himself, Vally is attuned to these vibes and in the time it takes to listen to the demo track, he not only decides to get behind Mohamed but also imagines the sound being expanded into a trio and has a pair of Dollar Brand sidemen in mind. A recording date is hastily scheduled.

For a kid from the East Rand, a trip to Johannesburg is a big deal and going to a studio to record an album has profound implications. Mohamed is not only aware that his album might be broadcast on the radio but also recognises that recordings travel through time and space and wants to put his best foot forward. His mother insists that he wear a jacket and tie and plans are made to collect his Yamaha organ despite the availability of a more advanced Hammond model in the studio. Mohamed knows his way around his own gear and doesn’t want to chance it.

The trio that assembles in Gallo’s eight-track studio in July of 1975 to record Black Disco’s self-titled debut is a profoundly South African constellation plucked from three different cities. Saxophonist and flautist Basil Coetzee is from Cape Town and is heralded as the rising jazz star who plays on Dollar Brand’s hit track. Barely a year since the album’s release, he is now widely known by the enduring stage name Basil “Mannenberg” Coetzee. On bass, Sipho Gumede is a young Zulu session player originating from Cato Manor in Durban. Mohamed recalls admiring him from afar at Dorkay House and is aware that he’s involved in the maverick Roots ensemble (which will later evolve into Spirits Rejoice).

The recording process is organic. Vally has brought the ingredients together and lets the artists take the floor, easing into a more passive role beside engineer Peter Ceronio in the recording booth. Mohamed is ostensibly the bandleader but an egalitarian approach emerges, embracing input and direction from everybody involved. He is in awe of his experienced sidemen but the respect is mutual with Coetzee remarking that his compositions are original and fresh and Gumede admiring his unique and unpretentious playing style. The band begins to run through the material and the connection the instantaneous. Gumede suggests that the engineer start recording and some of their rehearsals are even selected as master takes.

Albeit just a recording project, a name for the group is the subject of enthusiastic discussion and when Mohamed fields the idea Black Disco, the name is unanimously approved. Black musicians from the United States are in the vanguard of global popular music and a new style called “disco,” by way of Donna Summer in 1974, expresses the most cutting-edge manifesto for R&B and soul. The name Black Disco is thus a bold expression of Afrofuturism but as disco takes an unexpected trajectory into mainstream pop, the band will come to outgrow its name. Reissued on CD in the 1990s, the word disco carries so much Saturday Night Fever baggage that Vally promotes the band under the banner Black Discovery instead to avoid confusion for new audiences.

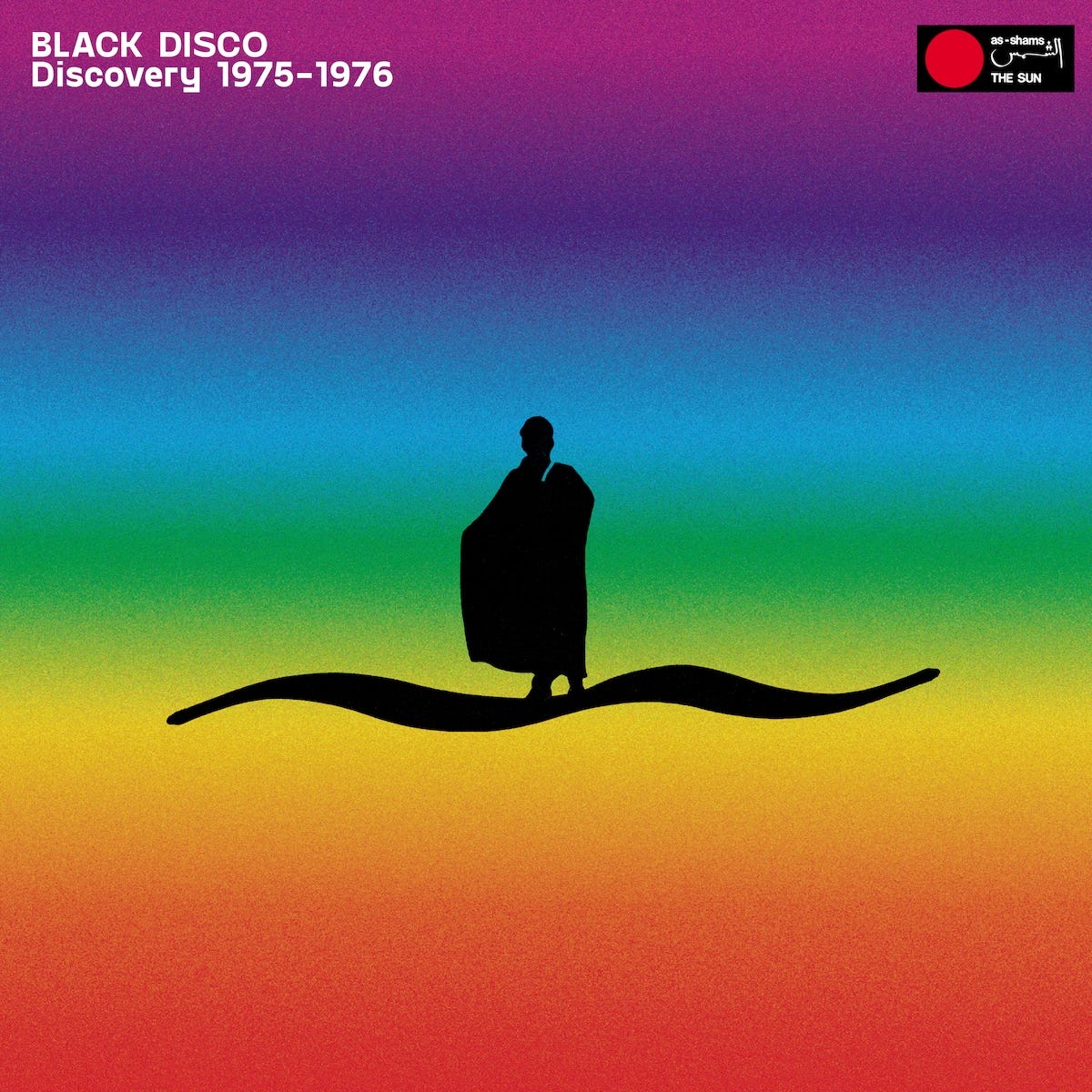

In additional to a striking name, the project also requires a memorable visual identity. Vally is a friend and patron of a number of artists who orbit the music scene and commissions works from the likes of Walter Saoli, Mafa Ngweya and Hargreaves Ntukwana to craft a look and feel for his catalogue. His brother-in-law Abdul Kader, an illustrator and design enthusiast, is tasked with creating the iconic As-Shams/The Sun logo. While pondering the art direction for Black Disco, Vally looks through Kader’s portfolio of doodles and sketches and stumbles upon the striking image of a silhouetted figure in a long coat. The anonymous solitary figure is a perfect fit for Black Disco – a graceful subject inhabiting a surreal landscape with the stoic presence of a wise man or shaman.

To bolster the concept, Vally writes a poem for the back cover of Black Disco’s self-titled debut that he attributes to the unnamed “Street Poet.” The figure will be a visual thread that runs through the Black Disco series and an emblem that Pops Mohamed carries throughout his career. The back cover also has a stick figure drawing of a man seated at an organ with a caption reading, “Hey Pops, you’re sliding from the chair.” The drawing is the work of Vally’s young son, who attends part of the session and is mesmerised by the animated way that Mohamed plays the organ, contorting his body to step on the bass pedals with his left foot and manipulate the rhythm box expression pedal with his right foot while playing melody on the keys with his hands. “He looks like he’s about to fall off his chair,” says the young boy and his astute observation becomes a running joke.

A 1975 review of Black Disco’s first offering frames the album as “another masterpiece” from As- Shams/The Sun. “It opens with the combination of flute and organ which leaves you breathless. It’s smooth and drives your soul crazy. The two build up their tempo and the flautist moves into a fascinating solo,” reads the enthusiastic review, adding that, “Basil Coetzee turns the flute into a talking instrument. It’s beautiful, you’ll dig it.” But not all the feedback is positive and another critic thinks that Coetzee’s saxophone squeaks. “Don’t take too much notice of these people,” advises friend and fellow-saxophonist Barney Rachabane. “A saxophone is like a human being, it farts. It’s quite natural if you fart. If you don’t squeak, it means you’re too clean.”

Black Disco’s second album follows in 1976. Having run its creative course, the drum machine is replaced by Peter Morake, a Sipho Gumede compatriot from Roots. The presence of a drummer raises the band’s game and leads them into more adventurous territory. The album’s title track “Night Express” is a rare composition from Basil Coetzee that channels the South African jazz motif of a train – evoked most famously as the indifferent, mechanical proxy handling migrant labour on behalf of technocratic industry in Hugh Masekela’s “Stimela (The Coal Train)” in 1974. On “Night Express,” the train is a funk juggernaut driven by an unrelenting bass that emits piercing flute whistles, soulful choral chants and rapturous sax cries.

Black Disco 3 also appears in 1976, featuring “Mannenberg” drummer Monty Weber on this occasion with founding member Sipho Gumede absent owing to his unrelenting schedule. Peter Odendaal (recording as Richard Peters) steps in on bass, becoming a contributor who goes on to work alongside Gumede when the core trio evolves into Movement in the City in the 1980s. Like both of its predecessors, the mostly original album includes an arrangement of a well-known popular title for commercial leverage, this time exploring Procol Harum’s psychedelic dirge “Whiter Shade of Pale” from 1967. “Spiritual Feeling” from the band’s debut is successfully revamped as “Spiritual Feeling Riding the Blue” but “Dawn” is the centrepiece – a trippy, flute-driven awakening of soft light, gentle colours and stirring creatures that starts the day, opens the album and unfolds over a period of ten minutes.

That the Black Disco sound is characteristically mercurial is partly due to the material not being developed through repetition in live settings. Vally’s keep calm and carry on approach to recording is also a factor. When Mohamed identifies an issue with a take, Vally promises to fix it in post-production to move the session forward. Imperfections occasionally slip through the gaps and find their way onto the records but so too does the improvisational authenticity of the performances. For many, the raw honesty of the Black Disco recordings is what holds their appeal. In contrast to the radio-friendly nuggets of tightly produced township soul that come from the major labels, As-Shams/The Sun brings a new type of jazz long-player to South Africa’s popular music marketplace with meandering tracks that occasionally occupy an entire side.

Black Disco released a solitary seven-inch single and a trilogy of albums on As-Shams/The Sun during the band’s brief existence from 1975 through 1976. In the twenty-first century, these recordings have crystallised into timeless, vivid and enchanting musical documents. The magic formula of Mohamed, Coetzee and Gumede traversed the 1970s, emerging in a new guise briefly as B.M. Movement and then Movement in the City for two new albums that stretched their sound in new directions in the 1980s. Mohamed and Gumede even continued working together in the 1990s on a series of recordings issued on the imprint Kalamazoo, drawing inspiration from the Reiger Park neighbourhood in Boksberg in the tradition of “Mannenberg.” For Mohamed, now in his 70s and still active as a composer and performer, Black Disco was the start of a music career that has spanned 50 years. “We believed in the music,” he recalls of working with Coetzee (1944-1998) and Gumede (1952-2004) in the group that has most shaped his creative life. “They’re still a very big part of my life. Whenever I write new songs, I always have them in mind.”